At the Center for Health Media and Policy’s inaugural event Monday night, “Media, Policy and Harm Reduction”, a number of experts were brought together to discuss harm reduction issues in media, policy and practice. CHMP’s visiting scholars, Juanita Maginley and Fiona Gold, from the Vancouver Street Nurses joined fellow panelists Dr. Daliah Heller, Assistant Commissioner, Bureau of Alcohol, Drug Use Prevention, Care and Treatment for New York City; Dr. Chinazo Cunningham, a physician practicing at a community health care center with a needle exchange program in the Bronx; Allen Kwabena Frimpong of the Harm Reduction Coalition in New York, an advocate with extensive background in international issues of harm reduction, especially among youth; and Maxine King, outreach coordinator for WORTH (Women On The Rise Telling Her Story), a substance abuse counselor and social worker who has experienced the health care system both as an addict and as a healer.

There were a number of key themes discussed throughout the evening. The last blog post was about the importance of humanizing people living with drug use in the media, as discussed by the panel. This post concerns the health care system and policy issues surrounding harm reduction and health care access.

This topic of discussion began after Ms. Maginley showed a 12-minute clip from the award-winning documentary “Bevel Up; Drugs, Users and Outreach Nursing,” which chronicles the Vancouver Street Nurses as they care for patients facing a variety of complex issues on the streets. The Vancouver Street Nurses perform patient assessments, care for minor injuries, and administer medications, such as antibiotics. Importantly, the Street Nurses provide a connection between their patients and other resources, such as community health centers, housing, detoxification programs, and mental health services.

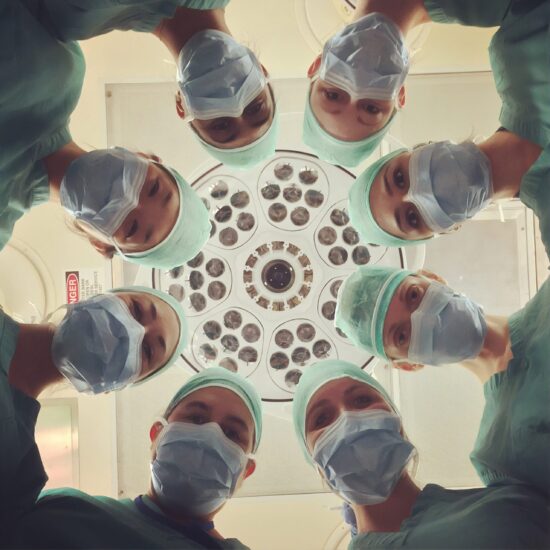

In stark contrast to the training the Street Nurses of Vancouver receive on harm reduction, Dr. Cunningham provided insight into her own experiences as a medical student. She said that throughout medical school and her residency she had only an hour of education on drug addiction; the material covered being the basic physiology of drug addiction, including how neurotransmitters work in the brain. This is a similar problem throughout most nursing and medical schools in the U.S., she said.

While providers are not trained on how to have conversations about drug use and addiction, neither, she says, are the drug users, themselves. With considerable social pressure to use the line: “I just want to quit using drugs,” this becomes the standard interaction between people who use drugs and any clinician they encounter. There is, in turn, little meaning or thought behind this. Programs, such as the Street Nurses, are exemplary in educating both health care providers and patients about how to have constructive conversations regarding drug use.

Dr. Heller made the point that use of Suboxone, a medication taken sublingually by a patient and used in place of methadone, would allow a primary care provider to prescribe this for patients, and then closely follow them and their physical health. Through enabling all providers to prescribe Suboxone for patients, drug users are provided with greater support, flexibility, and likely adherence to the regimen than could be possible in a methadone maintenance program. Dr. Heller also made the point that if drug use were thought of more as a medical issue this may also help to decrease stigma and encourage expansion of harm reduction programs, and therefore health, in drug users.

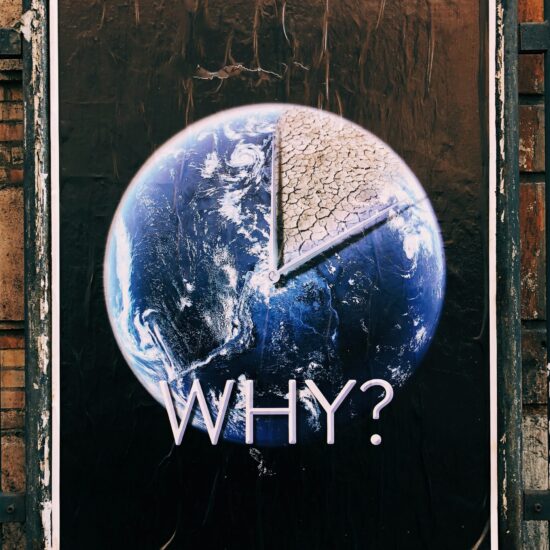

Ms. King concurred with the issue Dr. Heller raised about stigma. She relayed a story of being pregnant, drug addicted, and then treated horribly at an appointment for her first prenatal check-up. She said she “never went back” until she was in labor. Upon entering the hospital she was isolated in a room by herself. Again, she said she was made to feel like a kind of social “pariah”. The overarching theme here is that federal, state, city, university, and hospital policies around drug addiction create an environment preventing people who need care from receiving care. The overwhelming consensus of the panel and audience, alike was that we must increase the number of drug addicted persons who are linked to the care that they so desperately need by making changes in outdated, misinformed, and irresponsible policies.

Jen Busse, RN, MPH is an intern for CHMP and is currently working toward her MSN as a family nurse practitioner

Pingback: Harm Reduction or Stigmatization: What’s Your Approach to Drug-Addicted Patients? « Off the Charts / November 1, 2010

/