Last week I posted an interview with Seema Reza, a student of Transformative Language Arts at Goddard College who uses the arts with veterans and active-duty service members. This week I have interviewed Caryn Mirriam-Goldberg, the founder of the Goddard program and of the Transformative Language Arts Network. She leads community writing workshops in Lawrence, Kansas, and from 2009 to 2013 was the state poet laureate of Kansas. Caryn has written 16 books in various genres, including poetry, memoir, and fiction, and she and singer Kelly Hunt offer writing and singing workshops through Brave Voice. Make sure to scroll to the bottom of this post for a breathtaking poem and photo from her upcoming poetry-and-photography collection with Stephen Locke.—Joy Jacobson, poet-in-residence, @joyjaco

How did you come to the term “transformative language arts” (TLA)?

In 1998 when I was teaching at Goddard I started to realize how much students needed to write about their own lives in order to do strong critical writing and creative writing. And I was leading writing workshops in the community, a group of low-income women at a local housing authority and workshops in the schools with teens. And it started to occur to me that we had music therapy and art therapy but no parallel with writing. At Goddard I realized it’s much broader than therapy and much broader than writing. It also includes spoken word and theater and collaborative or solo performance—all the things we might do with words artistically to have some impact on improving the world. Deciding what to call it was really difficult. I had a contest with no real prizes. Someone said “transformative practices” and someone said “language arts,” and while it’s a mouthful transformative language arts names it in an open and accurate way.

The program offers a master’s degree at Goddard.

It’s been a master’s program since the fall of 2000. We’ve had about 70 graduates. Most who’ve gone through it are making a living in TLA in some way—coaching, teaching in a variety of settings, leading arts-based community-building projects, and so on.

You said it involves language but is more than writing. Can you say more about that?

It really became clear how much in our culture and in academia especially we split everything up. People in the oral tradition are in the classics department. People interested in social change are in political science or social work. And creative writers are in creative writing departments. That seems to me to be a false set of divisions. We’re diminishing the power of our words by categorizing them in these ways. There are all kinds of things we can learn from one another, by having a more interdisciplinary approach.

Did you encounter any resistance at Goddard when trying to set it up as an interdisciplinary program?

I had the great advantage of founding TLA at an interdisciplinary college. Many colleges and universities are developing more interdisciplinary approaches. But Goddard is based on progressive education and the work of John Dewey, which says that you know best what you need to learn and how to do it. Looking at something from many angles is one of the best ways to get a fuller picture of it. In all of the Goddard programs students are required to look at what they’re studying through different lenses. TLA students have a core reading list and those areas include the oral tradition, creative writing, traditions of social change, psychology as it relates to facilitation, and how not to step into the role of therapist when you’re not a therapist.

I faced resistance at Goddard and outside of Goddard for one simple and difficult question: what is and what isn’t TLA? When defining an interdisciplinary and emerging field it gets confusing. A student who is working with poetry and studied poetry therapy and facilitates workshops for elders, her work could be poetry therapy, applied creative writing, or a form of narrative theory. TLA is like a big tent that overlaps all of this. I think of it simply as a clearing in the woods. People who resonate with it gather there and we draw from what everyone is bringing to that clearing.

What a lovely image. I feel like I just stepped into that clearing.

That’s where community comes in. So someone like Seema Reza is starting the TLA master’s program, and she’s already doing workshops with wounded warriors and is an accomplished writer. I’ve had folks in the program who’ve had long careers as teachers, nurses, psychologists, librarians. They’ve been working in their hearts and communities and writings on something related to TLA their whole lives. One writer in Minnesota in her late 60s is doing the TLA program after retirement. For so many people who resonate with TLA, it names what they have been moving toward their whole lives as a writer or storyteller working with others around social change. That individual practice dovetails with community practice. What are you doing to make and keep community and foster healthy communities? I’m such a big fan of therapy that I should be an honorary therapist. But for many of us that deep inner work with a guide, while essential, is just one part of it. The other is finding “your place in the family of things,” as the poet Mary Oliver puts it, your place in community.

Can you give an example from your own life?

I was an artist as a child. I drew constantly, I painted, I was totally into the visual arts. When I was 14 my parents had a long and horrendous divorce. On a dime I switched to writing. There’s an old Yiddish saying that you can survive anything if you can give it a story. I became a poet. One of my first books was on writing for teens, even though I went into teaching and write in other genres besides poetry. I started leading writing workshops in my community in Lawrence, Kansas. The people who came didn’t come to learn to be “writers”; they came to see what the writing could show them. TLA came as a result of my seeing the deep need for people to write their stories and have good witnesses.

When I first started developing it I had no idea that there were other emerging groups naming similar approaches, such as Healing Story Alliance, the National Association of Poetry Therapy, and Theatre of the Oppressed. The more I learned about TLA-type things, the more I came home to who I am and what I am supposed to do with my life. Many people involved with the TLA network are there for the same reason. We’re all about wanting to do something about the brokenness in the world and to connect with our communities.

It sounds like that notion of bearing witness is an essential part of it.

Yes. I had a teacher named Judith Rance-Rooney, a really young teacher who led this special writing program for students who were in agonizing home lives. We were reading Beowulf in sophomore year of high school and I didn’t understand any of it. She told me “I know you tried so I’m going to give you a D.” But then she asked us to write a sonnet. From there I would sit with her in the teacher’s lounge with my new poem every day. She was able to witness who I was and what I was saying even if it wasn’t written that well. I was born hard-wired to create. I could have gone into music or visual art, but writing was what I needed at the time.

I teach an online class through the Loft in Minnesota on the craft of poetry, and I find that where the writing leads us is often more important than the actual writing. Developing the craft of a piece of writing gets you to a spiritual or communal breakthrough you need but it’s often not presented in writing courses that way.

In a lot of MFA programs and writing conferences there’s a real setup for competition. I’ve been to writing conferences where everybody’s lining up with what they perceive as the best poet and vying for validation. There’s the sense that there’s just one pie and there’s so many of us; some people are just going to get bigger pieces. TLA’s answer to that is to bake more pies. In the literary world it’s a whole different story. It reinforces the sense that there’s only a little room for the places at the top and tens of thousands of people are vying for them and won’t get them. TLA’s focus on right livelihood steps outside of that lottery-ticket approach to who’s going to make it as a writer.

You’ve written in a lot of different genres. Why have you chosen to write about your life in poetry and fiction and nonfiction?

Creating can make us feel more alive. My novel The Divorce Girl is a semi-autobiographical story of someone making her way through her parents’ divorce by making art and making community. My main character is a photographer, not a writer, and also is much taller than me. I have five books of poetry and a memoir called The Sky Begins at Your Feet, about how community and a connection to the earth helped me heal during my bout with cancer. I would hand my doctor piles of journal entries, and he would put it in my medical file; that became the basis for this memoir. I just finished Home on the Range, what I’m calling a “memoirette,” about my four-year term as poet laureate and how with the crazy politics in Kansas at the time all these writers around the state made community.

What do you find when you return to poetry?

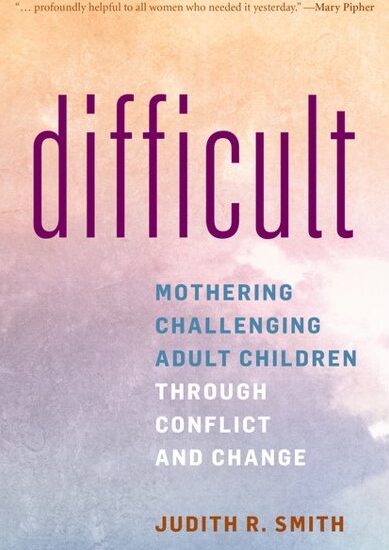

I have been immersed in poetry lately, a book of poems on the weather. I partnered with a storm chaser, a photographer named Stephen Locke, and our book of poems and photographs will be called Chasing Weather. With poetry it’s a slightly different approach. Some poems are not narrative; they’re more lyrical. To paraphrase William Stafford, everything has a song if pitched just right. Poetry is my spiritual practice—to pay attention, open up my perception, see what’s right in front of me. We live in a culture where it’s easy to ignore what’s in front of us. For example, the bird feeder outside my window right now is being mobbed by a flock of red-wing blackbirds. Poetry is a way of learning to observe, of using the best words I can to convey that to others.

The following poem by Caryn Mirriam-Goldberg and photo by Stephen Locke are excerpted from Chasing Weather. Thank you, Caryn.

Questions for Home

Did you imagine there was more than this?

More than the grass or the sky?

More than the quick touch of a six-year-old’s fingertips

on your sleeve? Did you believe it would add up

to a history of torrent and mathematics,

ultimate meanings, causes and effects intersecting

like constellations of the greatest minds

you never knew?

It’s just a gravel road in the country.

An edge of grassland washed out of its redness.

It’s just a bobcat you missed because you opened the door

a second too late. The breeze inside the breeze,

the dominant gait of weather, the green light in the distance.

Here, don’t be afraid. It’s not like you lost anything

but the craving for craving, and even that will return.

Where else would you rather be than right here

where the bluebird blurs past the cedars

and time sheds its old skin so its new one can form?

Photo by Stephen Locke

Pingback: Baking Pies & Introducing Gems | Transformative Language Arts Network Blog / December 12, 2014

/