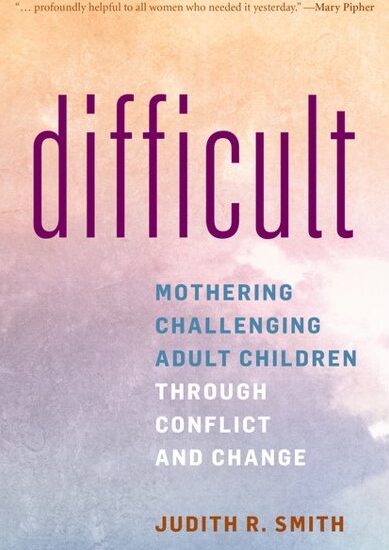

Over the years that I’ve been writing about health care through a nursing lens, I am always impressed, if not outright astounded, by the work being done to further public health. This month, the American Journal of Nursing has published my latest article, “A Cure for Gun Violence,” on a successful epidemiologic model for curbing urban violence.

In 2013 Gary Slutkin, the founder of Cure Violence, gave a TEDMED talk in which he describes how “clustering” works in the spread of disease—and of violence, especially shootings: “The greatest predictor of a case of violence is a preceding case of violence,” he said. In other words, a shooting can have the same effect on a community as any contagion, spreading by close personal contact.

Cure Violence works to interrupt retaliatory violence by training community members to intervene on violent situations, especially in the aftermath of a shooting. This process is powerfully depicted in The Interrupters, an award-wining documentary. After disrupting transmission, the work shifts focus to educating communities, with a goal of establishing new norms for interacting and resolving conflict.

Cure Violence has reduced the number of shootings and deaths from 41% to 73% in the seven Chicago neighborhoods where it was used. Other cities have shown similar successes.

For my AJN report I talked with nurses and others working with Aim4Peace, a Cure Violence affiliate in Kansas City, Missouri. That program’s director, Tracie McClendon-Cole, told me that although some may scoff at the idea of preventing and treating community violence as a contagious disease, they appreciate it when it’s explained to them. She said:

We look at violence disease-colonies the same way we look at cholera disease-colonies. It’s a scientific approach, not a moral one. We’re looking at the brain and behavior and how the disease of violence is transmitted, how it affects group function.

A study published this month in Pediatrics demonstrates the need for this kind of approach. Young people seen in an urban ER for assault-related injuries showed a much higher risk of becoming involved in subsequent violence. Carter and colleagues followed two groups for two years. All were young drug users: one group was seen in the ER for assault-related injuries and the other was not. The researchers found that 59% of the young people treated for assault were involved in firearm violence in some way in the following two-year period, almost all of them as victims—threatened, injured, or killed by guns. Nearly a third were aggressors, as well.

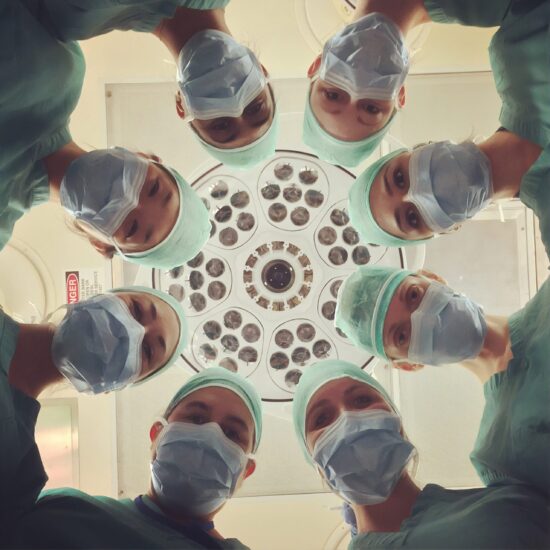

Preventing retaliatory violence is where hospitals can intervene, to profound effect. One recent study (abstract here) showed hospital violence-intervention programs to be effective in reducing rates of injury and reinjury, as well as costs. Those researchers recommend that such programs be implemented in all trauma centers. I’ve gathered some resources for health care providers and others who may want to look into starting such a program.

The National Network of Hospital-based Violence Intervention Programs consists of more than two dozen programs working “to stop the revolving door of violent injury in our hospitals.” The Web site features support materials for starting a hospital program.

Violence Is Preventable: A Best Practices Guide for Launching and Sustaining a Hospital-based Program to Break the Cycle of Violence, produced by Youth ALIVE!, encourages nurses and other clinicians to expand their patient advocacy to encompass policy advocacy.

Preventing Youth Violence: Opportunities for Action. This 2014 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention proposes that violence against children, teens, and young adults isn’t inevitable and recommends a strategy of collaboration among educators, public health professionals, religious organizations, law enforcement, and business owners.

Contagion of Violence: Workshop Summary. A 2012 Institute of Medicine Forum on Global Violence Prevention convened a workshop to explore the “epidemiology” of violence, including modes of transmission and strategies for interruption. The book is available for free download.

And check out this Cure Violence video that explains the model and shows Aim4Peace community workers in action.

josephineensign / April 17, 2015

While I like this idea and approach to violence prevention, it has some serious flaws. For one thing it seems to mainly be a top-down approach (and mainly by highly educated/affluent/well-meaning/white people) to ‘contain the spread of dis-ease/contagion’ arising from less educated/impoverished/ well-meaning/frustrated/people of color. It doesn’t acknowledge and address the high rates of income inequality (and imbedded racism/classism) that is the best predictor of homicide/firearm deaths in communities.

/

s / April 17, 2015

Joy:

A big congratulation for calling Cure Violence to the attention of a wider audience in such an important, high profile journal. This project, as well as the larger concept of considering violence in the context of the epidemiological model – a notion that Dr. Gary Slutkin has championed — is something that should be studied, widely taught, and even – to use a word that doesn’t show up much in our line of work – celebrated.

Celebrated?

Doctoral training in criminology, often taking place in one of the major disciplines in the social and behavioral sciences, rarely provides occasion for celebration. And that’s not because we lack good news about decreasing crime rates and effective prevention strategies. The public may never stop believing that the world is always getting more dangerous, but there are programs and policies that do work. Sometimes that effectiveness is revealed in real world observation (ethnography), and sometimes – despite the almost intractable problems of using statistical methods to study messy, real-world situations – studies actually show causal links between something you do and the quality of society you end up with.

But, as everyone from a first-year statistics student to a distinguished epidemiologist knows, actual causal links are notoriously difficult to prove, especially when we study our world and ourselves. I wonder how many people know just how much they drive behavioral scientists crazy simply by moving through their day as if linearity was a concept yet to be discovered.

And then there’s the pollution problem: the popular media are positively littered with pseudo-experts using pseudo-science — and sometimes political leaders relying on that pseudo-science – to tout single, magic cures for everything from homicide rates to flooded basements. Just turn on 24-hour cable TV news in the aftermath of a high-profile violent crime and hear the certainty with which some amateur profiler solves crimes and solves social ills, and that’s before we even know what actually happened.

So what’s to celebrate?

Some things really work! Which gets us to Cure Violence.

The last people you will ever get to admit that a community program, enforcement strategy, or change in sentencing policy has reduced crime are real scientists who study crime and violence, the hard-nosed, evidence-based practitioners of everything from time series analysis to Bayesian regression. Show me a politician from any political party who claims that a recent drop in crime is due either to his or her toughness (Lord save us from the self-proclaimed tough ones!) or to one single miracle program they thought of on the treadmill, and I’ll find 10 of those scientists — statisticians, epidemiologists, psychiatrists, sociologists — with elevated blood pressures at the thought that any responsible official could be so clueless about causation, correlation, confounding variables, and all the rest.

Which is why it’s a shame that so few people know about Cure Violence, which I came to know through its Chicago CeaseFire program.

This is not to ignore the spot-on criticisms offered in the comment above by Professor Ensign. This work, as it evolves, will not come close to its full promise if it does not fully account for stubborn, systemic variables such as racism, sexism, and income inequality. A “successful” program might look very different when seen from the vantage point of those in groups with every reason to mistrust interventions, including GLBT people, diverse immigrant groups, juveniles, the disabled, women, and others.

I disagree, though, when Professor Ensign seems to suggest (I may misread this. If so, I apologize.) that borrowing valuable concepts and methods from epidemiology makes it inevitable that old, vile notions of disease and poverty as evidence of social pathology or moral deficiency will surface. Any researcher using an epidemiological perspective who allows this to pollute their work, or who even subtly hangs on to the paternalistic notion that “we’ve come down from Olympus to help,” is simply a bad scientist doing even worse science.

Chicago CeaseFire also introduced Dr. Gary Slutkin to many of us from other academic disciplines who have come to see the incredible ingenuity of this brilliant epidemiologist who, with a simple insight, shifted the very gravity of an enormous field of inquiry: Hey, maybe violence is like an infectious disease. Maybe homicide is criminology’s version of a MRSA infection? What if we treated violent assaults like pertussis? Things have never been the same.

And now, Joy, you’ve brought all this work, along with the extremely promising linkage of violence studies and epidemiology, to just the kind of healthcare professionals who need to know about it, many of whom see people every day whose bullet wounds and gashes and slashes are the ultimate proof of the failure of getting “tough” or handing out longer prison sentences.

I hope that as many of your readers as possible might take a look at the report that Wes and his colleagues did, as well as some of the work by Gary that fueled it. Like any serious researchers, they could not be more forthcoming about every possible limitation of the statistical methods they used and the findings they reached.

But that study, as well as several others that can be accessed on the Cure Violence website, have shown that programs like CeaseFire can make neighborhoods safer and bring research on crime and violence out of the tabloid talk circus and into the era of serious, evidence-based practice.

And that’s something to celebrate.

Best,

Steve Gorelick

Steven M. Gorelick, Ph.D.

Department of Film and Media Studies

Distinguished Lecturer

Hunter College

City University of New York

New York, New York 10065

Areas of Specialization:

Violence, Human Rights & Criminology

Sociology of Art/Media/Culture

Faculty, Hunter College Human Rights Program

MFA Program in Integrated Media Arts

/

mmb317 / April 18, 2015

Great work Joy. Thank you for bringing this unique approach to combatting violence to our attention. I work in Newark, NJ where the surrounding inner city violence floods University Hospital Trauma Center with gunshot, stab wound injuries, and murders. Revenge is often at the forefront of some surviving patients, their friends, and their families.

Another unique initiative that I heard of by word of mouth (I apologize for not knowing the name) attempts to alter perceptions between police officers toward individuals who reside in violent communities, and the communities’ perception of the police. Because the police tend to encounter the majority of individuals in disadvantaged communities under extreme and often violent circumstances, officers often develop negative assumptions about entire communities based on stereotyping. This initiative rotates police offers on and off the streets of violent communities in 6 month intervals. In the months that officers are off the street, they work in and around schools, churches, and other areas where they are less likely to encounter violence while learning about the positive aspects of the community in which they work. Community members may come to see the police as civil servants and dismiss their preconceived stereotypical beliefs about the police as well.

Although this is not quite the same as the topic discussion you’ve presented, in the wake of recent events violence must be addressed from as many angles as possible.

Thank you again for this blog entry.

Maria

/

djmasonrn / April 19, 2015

Great post and comments. What immediately came to mind is Patrice O’Neill’s Not In Our Town (niot.org) work. Patrice is on the Center’s National Advisory Council and Barbara Glickstein is on the board of NIOT. I’ve been impressed with this organization’s work to engage communities in speaking out to stop violence and hate. And I’ve long wondered why all schools don’t adopt the conflict management and peace curriculum of the Friends Schools. Need to provide children with a vision and tools for resolving conflicts peacefully.

/