This post was written by David M. Keepnews, PhD, JD, RN, NEA-BC, FAAN, Dean and Professor, Harriet Rothkopf Heilbrunn School of Nursing, Long Island University, Brooklyn, where he also holds the Harriet Rothkopf Heilbrunn Endowed Chair in Nursing.

The Washington Post recently reported something so bizarre that many of us had to re-check the calendar to make sure that—despite snow on the ground in many of cities—we hadn’t somehow time-warped to April 1. Or perhaps we had traveled backwards to 1984 for an early lesson in Newspeak? Either way, we appear to have traveled backwards, alright.

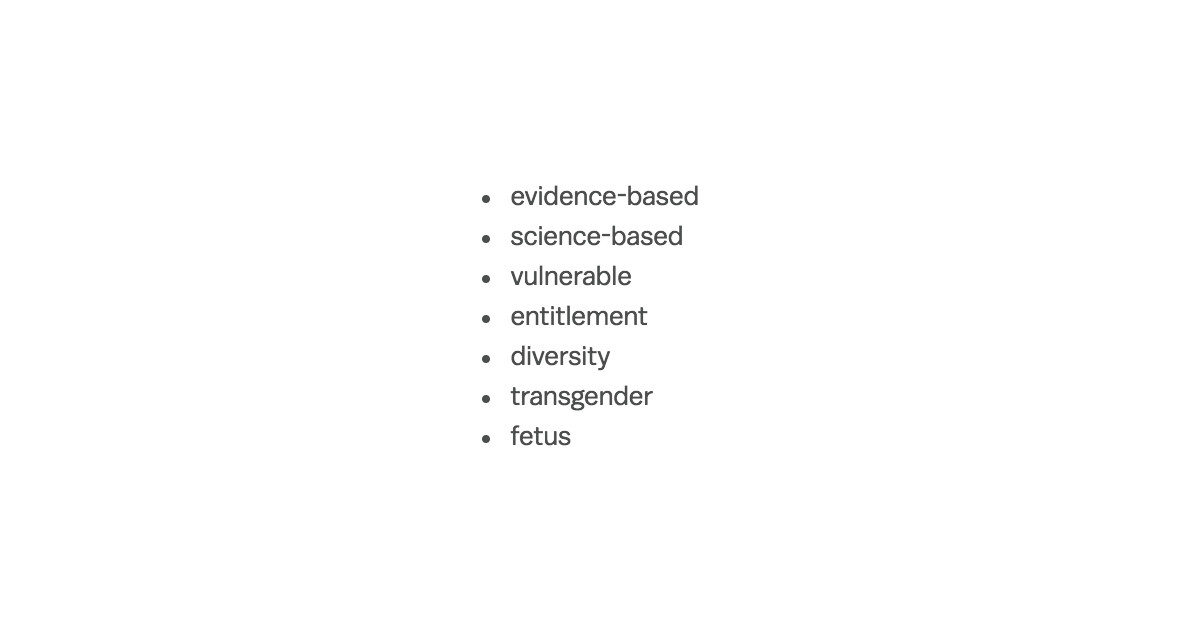

The story was that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) had “banned” the use of 7 words and phrases from use in the agency’s budget justification. Those words and phrases were: “vulnerable,” “entitlement,” “diversity,” “transgender,” “fetus,” “evidence-based” and “science-based.”

Really?

A public health agency muzzled and unable to speak to the needs of vulnerable populations? Unable to address the needs of diverse populations, including (but by no means limited to) transgender people? Unable to advocate for evidence-based, science-based recommendations and interventions?

A CDC spokesperson reacted strongly—saying that to claim these words were “banned” is a “complete mischaracterization.” My concerns might be assuaged somewhat by being informed as to what an accurate characterization would be, but no such explanation has been forthcoming.

To the extent that a backstory can be pieced together, it seems that the focus of these banned (forbidden? highly discouraged?) words and phrases is the CDC’s budget justification. It’s not clear where the edict (order? official glossary?) came from—from within CDC, from higher up in the US Department of Health & Human Services, or from elsewhere in the Administration. But the idea seems to be: Keep a low profile. Don’t let people know the CDC is addressing any high-priority public health issues, lest someone find them controversial and take it out on the agency’s funding.

I’m not naïve—really, I’m not. But if a leading public health agency is muzzled—by its own actions, or by higher-ups–by staying silent on public health principles and priorities, what’s the point? If an agency filled with health professionals and scientists can’t definitively state that its work is evidence-based and science-based, then public health has taken a giant leap backwards.

In case you think I’m being overdramatic (or if you think that this issue is confined to budget justification language), consider this: The New York Times reports that the CDC, in eschewing terms like “evidence-based” and “science-based,” prefers saying that the “CDC bases its recommendations on science in consideration with community standards and wishes.” In other words—recommendations that are evidence-based unless they conflict with prejudice, bias or other backward, non-science based thinking. This is the antithesis of public health. Evidence-based public health practice often means pushing the envelope and going beyond some communities’ “standards and wishes,” especially when those standards and wishes stand in the way of saving lives. Needle exchange (which has a complex political history, largely because of restrictions imposed by Congress, not by public health officials). Sex education. Safer sex. Narcan distribution. Hey, at one point distributing information on shelters for victims of intimate partner violence was viewed in some communities as interfering with the sanctity of the family. Political interference may limit the use of sound, evidence-based approaches to public health practice. But let’s leave political interference to politicians to try to impose (while we oppose it)—that’s far different from public health officials censoring themselves.

And, of course, community standards and wishes can and do change. Often, they change in large part because of the efforts of health professionals and scientists repeatedly showing that once-controversial measures save lives.

The Administration is also frowning on spending so much money on health care in other countries as part of its “America First” worldview—er, um—Americaview. This is baffling. As if we can combat current and emerging epidemics (HIV, Ebola, Zika, HIV, and who knows what else may be brewing) by keeping our heads in the sand. Maybe they think building a wall will keep out viruses. It won’t. I favor an internationalist approach that recognizes a common duty to eradicate deadly and disabling disease wherever it occurs. But even if I decided to put on blinders and care only about the U.S., I would still know that efforts to control epidemics in other countries is critical to protecting public health at home.

But of course, that’s an evidence-based, science-based approach. It might conflict with the “standards and wishes” of some communities. I’d prefer to educate those communities about this issue and about the need to address the needs of vulnerable, diverse populations (yes, including transgender people). I don’t believe in ignoring prejudice and ignorance—I believe in the power of education and persuasion—but I don’t believe in allowing them to prevent progress in promoting health and fighting disease.

And I feel the same way about muzzling public health agencies, regardless of who applies the muzzle.

Monday, December 18th 7:00 PM Update by author, David M. Keepnews, PhD, JD, RN, NEA-BC, FAAN, is Dean and Professor, Harriet Rothkopf Heilbrunn School of Nursing, Long Island University, Brooklyn, where he also holds the Harriet Rothkopf Heilbrunn Endowed Chair in Nursing.

UPDATE, Dec. 18, 2017: The CDC has strongly disputed the claim that it

has any banned words. “I want to assure you there are no banned words

at CDC. We will continue to talk about all our important public health

programs,” wrote CDC Director Dr. Brenda Fitzgerald in a December 17

tweet. In a statement she wrote “I understand that confusion arose

from a staff-level discussion at a routine meeting about how to

present CDC’s budget. It was never intended as overall guidance for

how we describe and conduct CDC’s work.”

As previous reports suggested, the “guidance” was regarding how to

describe the CDC’s work in its budget justifications. But this is no

small deal. And it doesn’t really change what I had written earlier:

regardless of who offered this “guidance” and for what purpose, it

involves steering the CDC away from language and principles that are

fundamental to its role in protecting the public’s health. Whether

this was an exercise in censorship or self-censorship–and whether it

applies solely to how the CDC characterizes its work in the context of

justifying its budget—doesn’t make that much of a difference. Because

words matter. And the message to avoid using words and phrases such as

“vulnerable,” “diversity” and “evidence-based” is a message to us all

about how this Administration views public health. I can understand

why public health officials would feel embarrassed by the revelation

about its “guidance” regarding these words and why they would seek to

minimize it or explain it away. But as the large-scale public shock

and outrage over this incident reveals, doing so won’t be so easy.

David Keepnews, PhD, JD, RN, NEA-BC, FAAN

Jeri A. Milstead, PhD, RN, NEA-BC, FAAN / December 20, 2017

JERI A. MILSTEAD, PHD, RN, NEA-BC, FAAN / DECEMBER 20, 2017

Dr. Keepnews has voiced a strong opinion that, I believe, is held widely by the nurse community. To even hint at censorship (budgetary, in-house, or system-wide) smacks of a dictatorial, ignorant, horrid approach to health–public and private. This ‘directive’ (or whatever it is) reflects the attitude of the present Administration (and that starts with the President) about the culture, values, and ethics in the United States that I cannot accept. I will stand with my nurse colleagues and everyone else who not only reject this heinous directive but who actively oppose this and other attempts to muzzle our Voice.

/