As I’ve written on the blog before, comics are a powerful tool for use in health care. The growing community focused on the rich intersection of comics and health, illness, and caregiving is known as Graphic Medicine.

Comics have several roles to play in health-based research, such as an educational intervention to be evaluated, for example, this study of comics as a tool for emergency room education, or as a methodology for doing research itself.

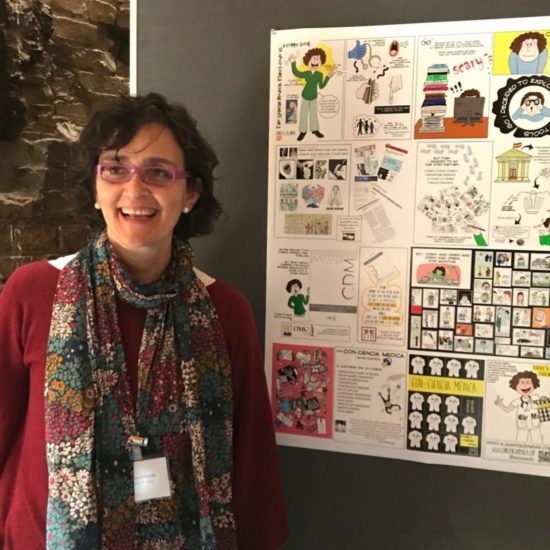

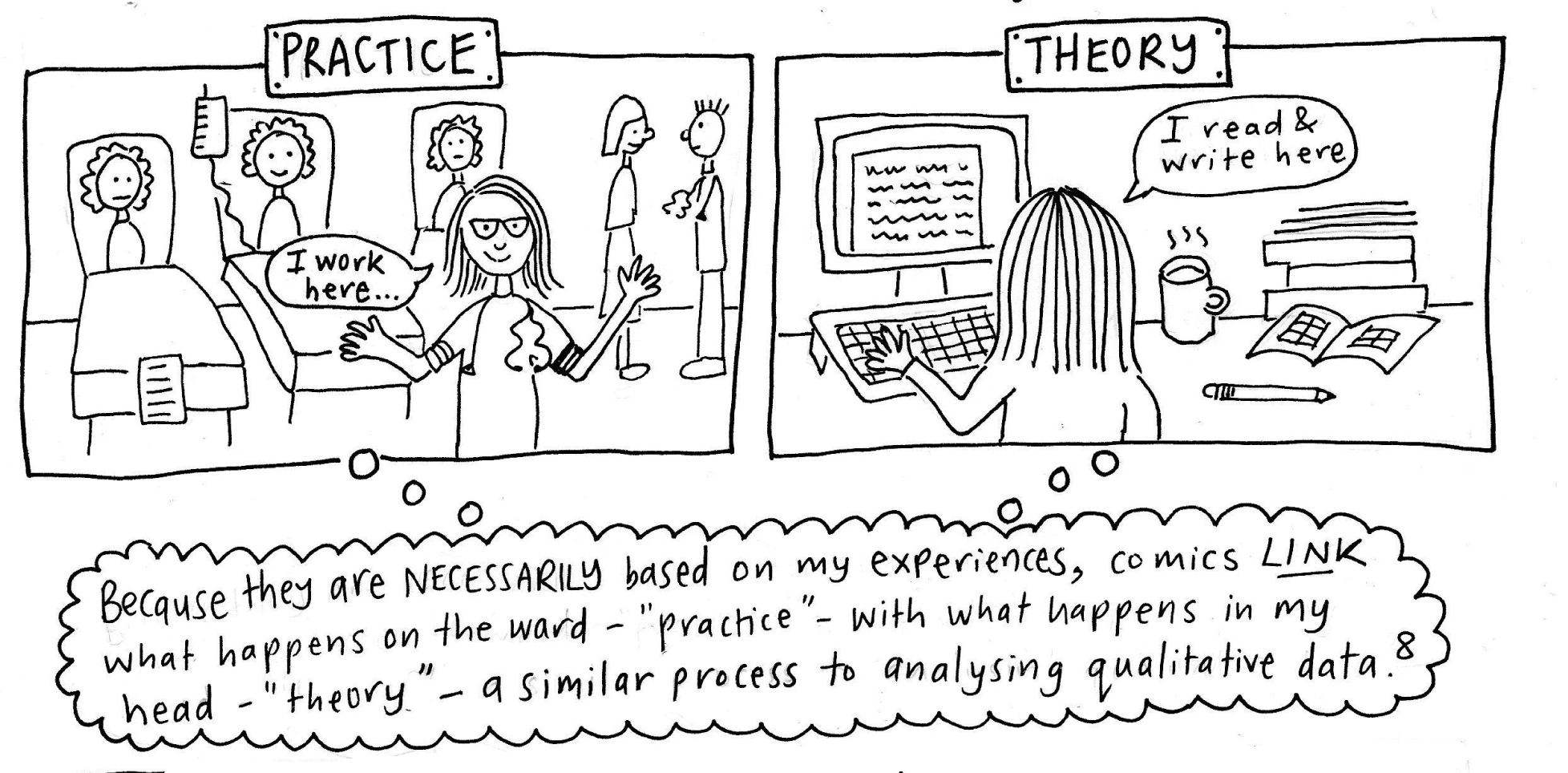

Geriatrician Muna Al Jawad describes how comics are, for her, a research methodology. Image courtesy of the artist. See citation above.

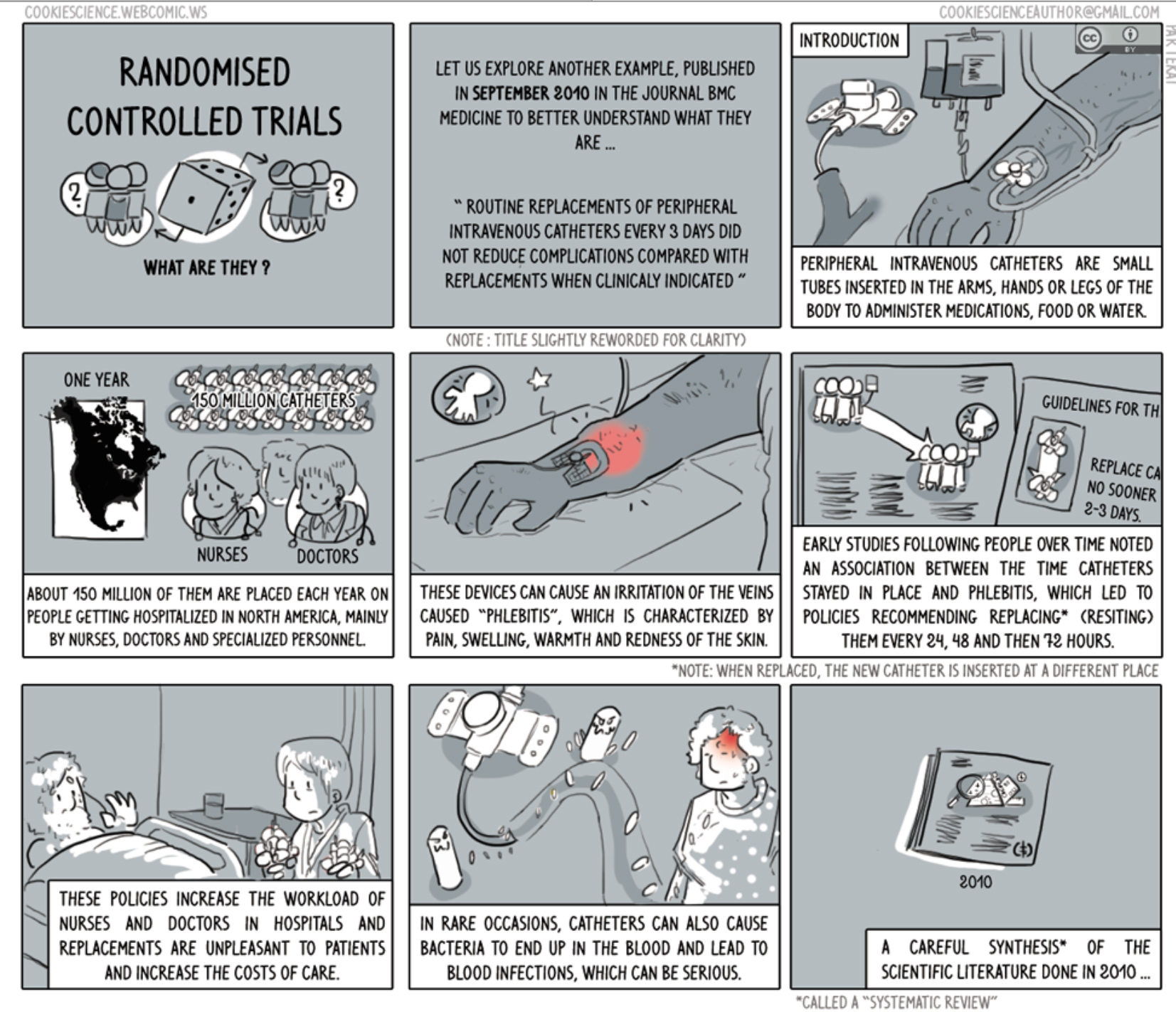

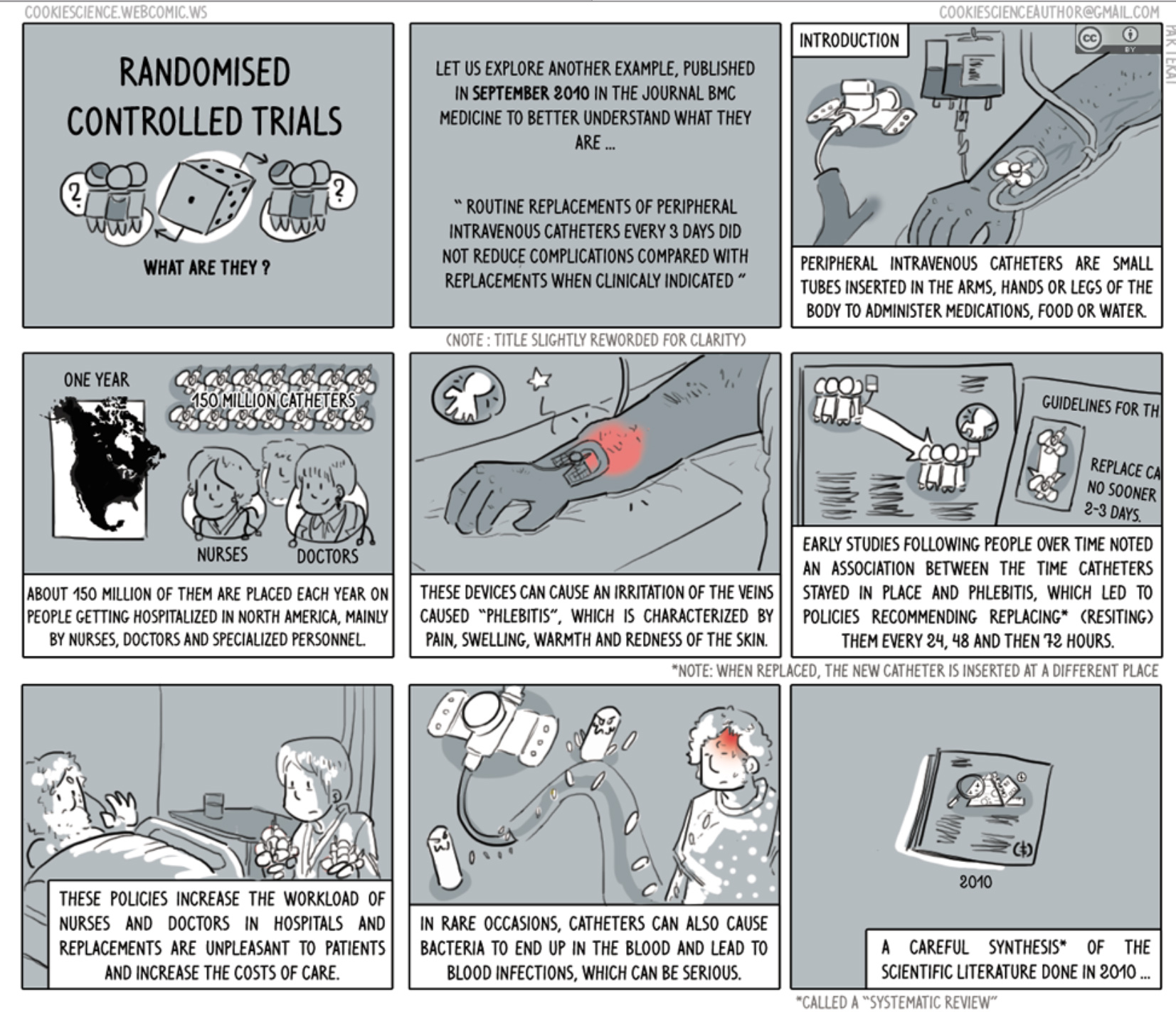

In this post, I’d like to focus on comics as a valuable tool for communicating the results of our research. Thanks to the great work of medical librarian Matthew Noe, I became aware of a comic called “Randomized Control Trials: What Are They?” created by Martin Vuillème (working under the name Tekai).Tekai’s comics are predominantly made in French, a tradition of comics known as bande dessinée, or BD. This comic in the series illustrates this research study relevant to many nurses, questioning the value of inpatient routine three-day IV site rotation. (If the comic at the link above appears tiny, click on it and it will enlarge.)

When I wrote to Tekai to express how thrilled I am with this work, he wrote, “I am pleased to know that you like them… although I’m sure my comics only look good due to few alternatives in the research-genre to compare them with.” He’s not right about it looking good only because there are few comparisons, the work is very strong. But he is right about the lack of work in this area. I can see so many applications for this kind of comic as an excellent way to disseminate our important research. Why is this kind of work so rare?

Perhaps it’s because health researchers are not considering comics as a legitimate means by which to communicate their research. We in the Graphic Medicine field hope to change that. The field of graphic journalism is growing, and health care reporting should take note. For a few stellar examples of graphic journalism, see this 2011 Atlantic article. Of special interest to nurses interested in policy and media work is number seven on that list, The Influencing Machine by National Public Radio journalist Brooke Gladstone, illustrated by John Neufeld.

A variation on the use of comics to translate research results are whiteboard videos, such as these examples by physician cartoonist Alex Thomas and health education specialist Gary Ashwal of Booster Shot Comics.

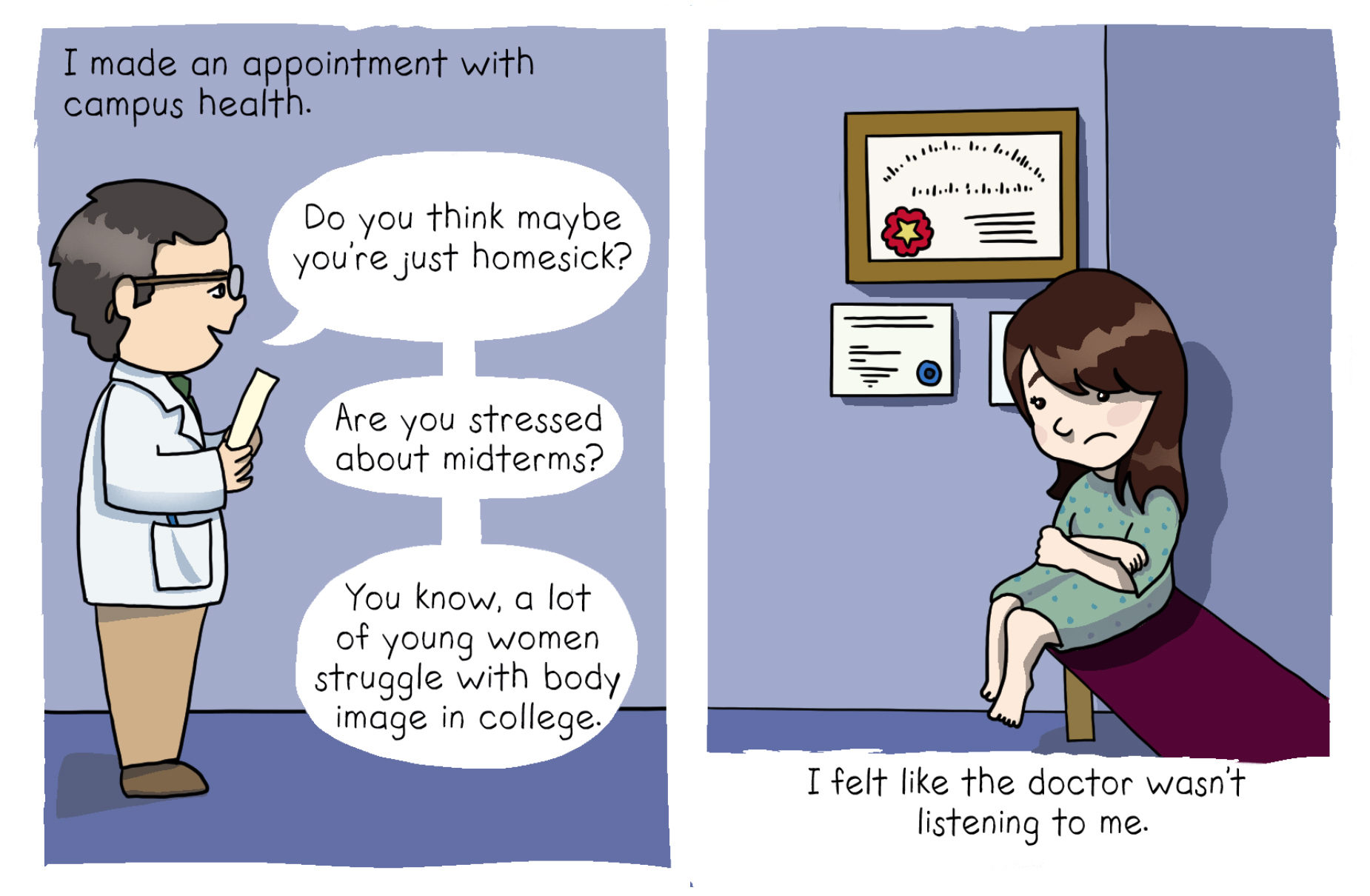

Another way comics can be useful in health research is to exemplify, using the power of narrative, the individual experience that a study seeks to illuminate. Consider this recent example comic by Aubrey Hirsch, “Medicine’s Women Problem” published last week on The Nib.

There is much data to support the claim that women’s experiences in medicine are unequal to those of men, that is, that a gender bias exists in medical care. Hirsch cites several of these studies at the end of her comic. But it is her story, presented clearly, visually, and supported by data, that is uniquely revelatory and compelling.

Bottom Line: Consider building comics into your research plan. When applying for grants, include a budget for paying a comic artist to work with you. Bring a comic artist whose aesthetic you like into your work as early as possible. If you would like recommendations for partnering with cartoonists, or simply finding cartoonists whose aesthetic and background might match your research goals, here are a few resources for connecting with comic artist in your area.

You can contact cartoonist/health care practitioners via Graphic Medicine. You can be in touch with the place that confers advanced degrees in making comics, the Center for Cartoon Studies in White River Junction, Vermont. You can attend your local independent Comic expos, such as Small Press Expo (Bethesda), CAKE (Chicago), MOCCA (New York), MICE (Boston area), Short Run (Seattle), TCAF (Toronto), Alternative Press Expo (San Jose area). Walk the floor, see who is doing science-themed work, or whose aesthetic you might like, and strike up a conversation about potential collaboration.

As James Sturm, co-founder of the Center for Cartoon Studies in White River Junction, said when discussing Graphic Medicine and his school’s applied comics program, “Comics are a blowtorch. So far we’ve only lit a few cigarettes.”