Let’s Help Every Senior Make the Most of Technology

At the American Society on Aging (ASA) conference in Washington DC, the mantra among many speakers was the same: technology’s role in caregiving is vital, and it’s growing.

Experts agree that to manage our ever-increasing senior population, they need to get wired – to access and learn how to use computers, email, social networking, and health information. To effectively do so, their tech literacy and comfort level must be raised. Most experts at the ASA conference agreed that accessibility and usability are two major barriers to overcome; without it, an entire population segment will be left out.

From looking up health information to Skyping with the grandchildren, to participating in social networks, going digital has many quality of life benefits. It also helps to improve cognitive function, memory, and reduce depression.

This is true not only for traditional computer use, but for other senior-focused technology as well. Entire industries are popping up to help seniors and caregivers better manage their health, improve communication, enhance literacy, and give adult children peace of mind about their loved ones’ health, safety, and quality of life.

I attended several presentations that highlighted innovative products such as watches to monitor vital signs, computers with touch screens, large type, and simple instructions, and sensors around the home to track movement, or lack of it.

These are good ideas that can certainly enhance well-being, and give adult children a sense of relief about their parents’ health. There’s only one problem with technology — it costs money. From equipment to setup to broadband access, technology doesn’t come cheaply. While families in middle to upper socioeconimic groups may be able to afford the setup and monthly fees; what wasn’t addressed, at least until I asked the question, was what is being done to help low income seniors and families?

The seniors that need these tools most – disadvantaged, homebound, low income, ethnic elders – seem to be outside of the target.

iPads may be a great way for seniors to get online, and FaceTime a wonderful tool to see the grandkids, but many seniors cite cost as one of the major barrier to technology adoption. For poor seniors that are home bound, the situation is even more precarious. Broadband fees are likely not part of their fixed-income budget. What is being done to help them access and adapt to technology — something that is almost an imperative in today’s wired world?

I also learned about several innovative pilot programs to help seniors learn computing skills, as well as efforts to address the needs of elderly that are aging in place. Many local elder service agencies have partnered with businesses, universities, and non-profits to set up and implement classes at senior centers and libraries. New products and services are available or in the pipeline to boost safety, security, and health management. I heard almost nothing about those elderly that are on the fringes.

We need to keep asking about them, and not stop until there are policies and programs in place to address their needs too.

At the American Society on Aging (ASA) conference in

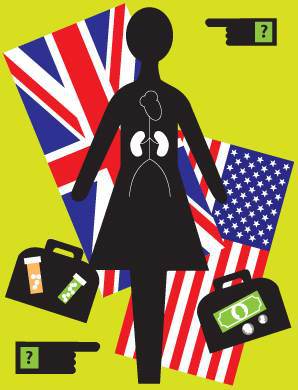

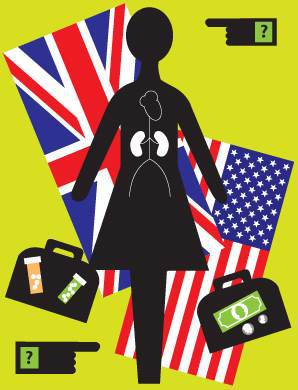

A few months ago, Bronx Health REACH and its 3 fellow REACH projects in New York played hosts to visitors from the UK who wanted to hear, see, feel and, where possible, even touch the work that we were doing in our respective communities to address the problem of racial and ethnic health disparities. For those who may not know, there are 40 REACH communities across the country who are part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s cornerstone effort to have local communities design and implement solutions to the health disparities in their respective community. Community can be a geographic location or a unique socio-cultural ethnic/racial grouping. REACH which stands for Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health focus is on eliminating underlying determinants through policy, system and environmental change.

A few months ago, Bronx Health REACH and its 3 fellow REACH projects in New York played hosts to visitors from the UK who wanted to hear, see, feel and, where possible, even touch the work that we were doing in our respective communities to address the problem of racial and ethnic health disparities. For those who may not know, there are 40 REACH communities across the country who are part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s cornerstone effort to have local communities design and implement solutions to the health disparities in their respective community. Community can be a geographic location or a unique socio-cultural ethnic/racial grouping. REACH which stands for Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health focus is on eliminating underlying determinants through policy, system and environmental change.