Story is an important part of healing. An entire sub-discipline in the health humanities referred to as narrative medicine has developed in the past thirty years in an attempt to understand, explore, and expand the use of story in health and healing. Sociologist Arthur Frank writes in his book Letting Stories Breathe: A Socio-narratology that our stories about our bodies and their troubles can actually care for us, by helping us formulate the courage to continue to desire from life, by helping to externalize our fears, and by helping us imagine our next viable selves, with and post illness.

Though both care givers and receivers alike can benefit from telling and hearing stories that help us heal, sometimes articulating our stories can be a challenge. Making and reading comics can be a terrific method for accessing our stories. (I’m defining ‘comics’ here as sequential art that conveys a narrative, often including text.) Based on a traditional panel framing, comics build one box at a time, helping us to focus and organize our thoughts and feelings. Comics combine word and image, and we know that different parts of our brains are in use as we do this, forging unique connections and pathways. Finally, comics can be fun – even when difficult topics are discussed.

Comics are an expressive medium, containing many genre. One of the genre to emerge quite prominently in the past ten years has been that of “Graphic Medicine.” This term was coined in 2011 by U.K. physician Ian Williams (author of The Bad Doctor) to refer to the interface between comics and the discourse of health. Three stellar examples of the variety and range of the genre are Peter Dunlop Shohl’s My Degeneration: A Journey Through Parkinson’s, Sarah Leavitt’s Tangles: A Story about Alzheimer’s My Mother and Me, and Brian Fies’s Mom’s Cancer. Fies has said of creating this book, “Comics were the right medium for the story I wanted to tell. They meld words and pictures to convey an idea with more economy and grace than either could alone.”

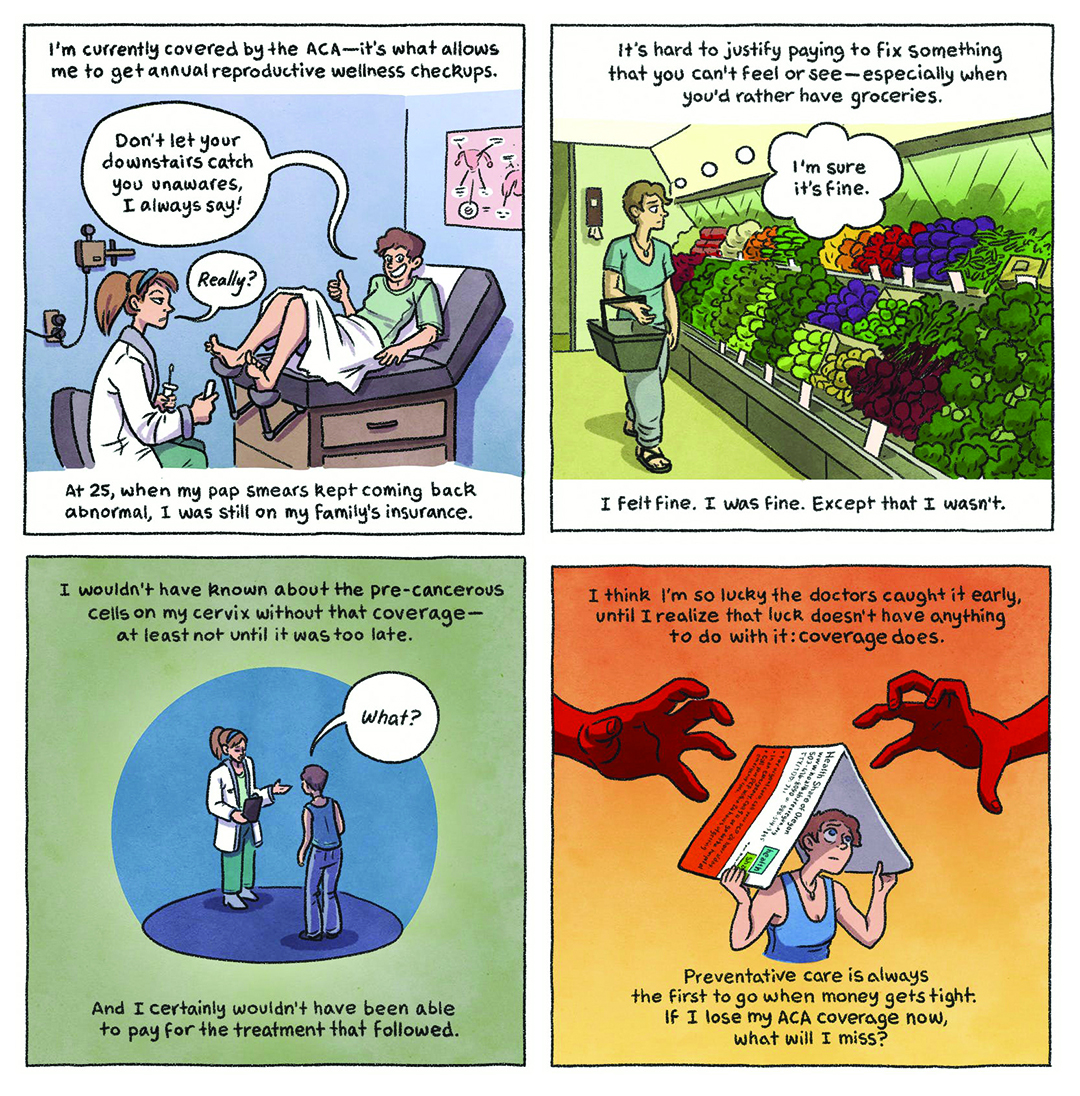

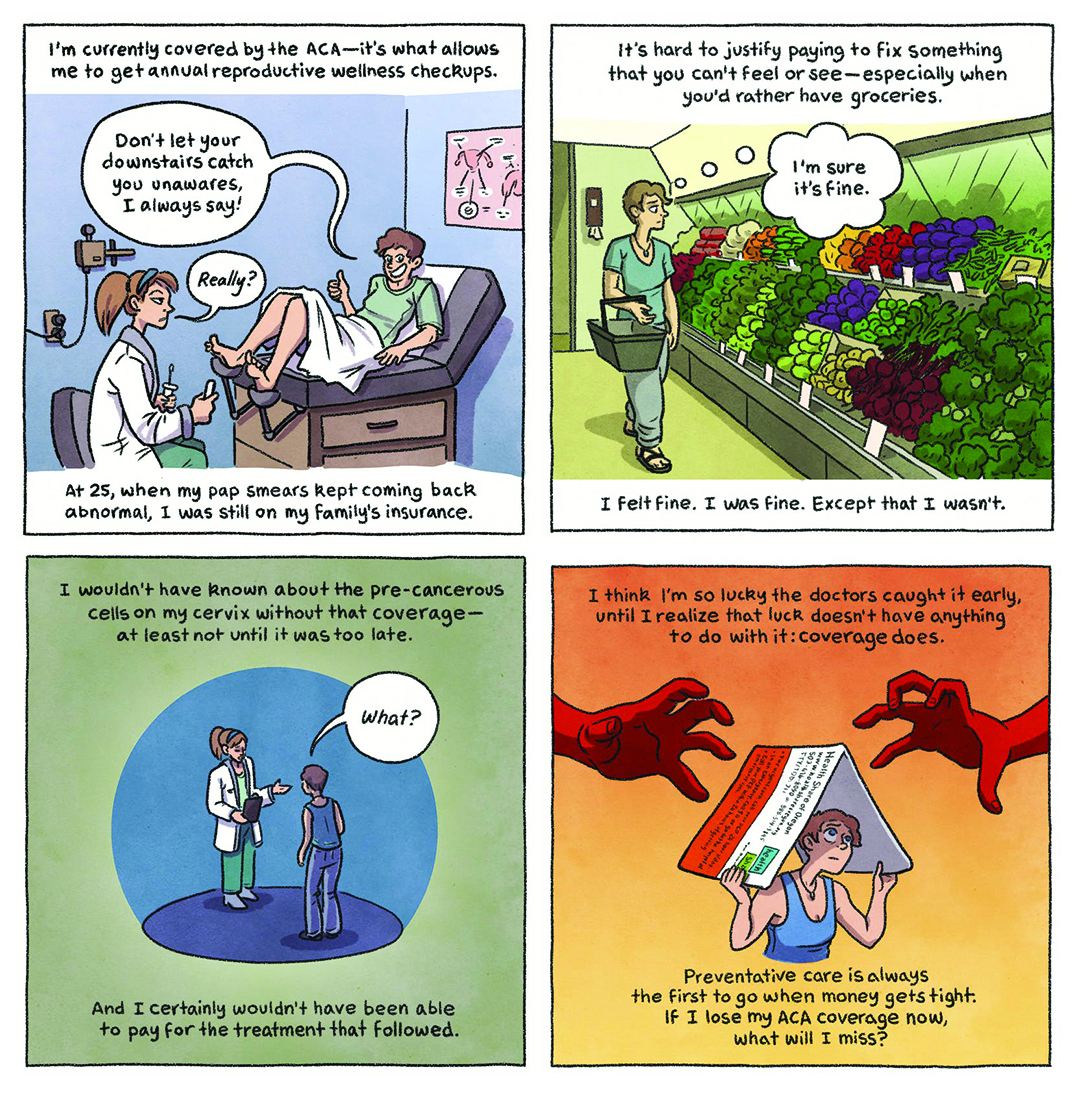

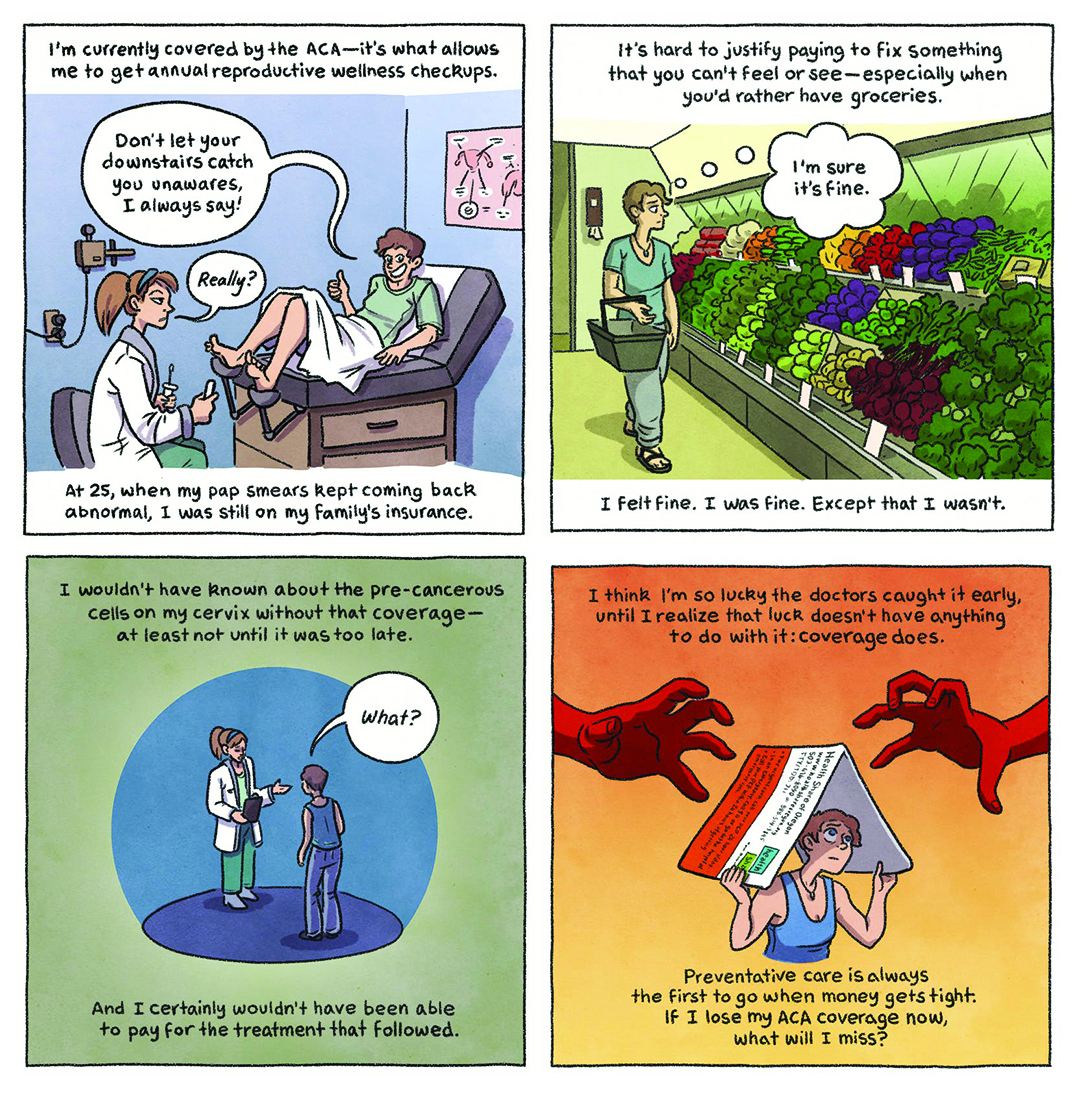

In Graphic Medicine, most often the works used in teaching are non-fiction memoir created by those living with illness and/or caregiving. Who better to represent the challenges illness can bring to lives, families, and communities? But those of us familiar with the history of medicine know that these voices are precisely the ones that have most often been marginalized. Physicians and other “experts” have traditionally defined and represented states of health, illness, and deviations from expected norms of the body. The underground history of comics is one that has created a space for bearing witness to stigmatized realities and amplifying the voice of the marginalized. Often these are our most vulnerable citizens, most in need of our health services, most at risk with proposed cuts to the Affordable Care Act. The new genre of comics known as Graphic Medicine can help by bearing witness to the stories of the impact of the ACA, those who will face the devastation its loss will bring to their lives. A series of four comics were posted last week on a website called The Nib, a website featuring political cartoons and non-fiction comics. The ACA comics were each individually titled, and the group was called “What Will Happen to Us? Four Cartoonists on A Life Without the Affordable Care Act.” The following example is by cartoonist Lucy Bellwood. Bellwood wrote on her blog about this comic, “I don’t talk about politics often. I like keeping my work accessible to a wide range of people. I’m also, if I’m honest, conflict-averse. But this so immediately and directly impacts my life and the lives of so many people that I love, that it seems like a good time to use the creative skills I’ve been cultivating to try and push for more awareness, more compassion, and more action.”

Bellwood wrote on her blog about this comic, “I don’t talk about politics often. I like keeping my work accessible to a wide range of people. I’m also, if I’m honest, conflict-averse. But this so immediately and directly impacts my life and the lives of so many people that I love, that it seems like a good time to use the creative skills I’ve been cultivating to try and push for more awareness, more compassion, and more action.”

Those who work in the public health domain know that comics are great educational tools when we face a high density of information to communicate, there is a high importance to communicating the information, and the learner is in a high-stress situation. Next time you are on a flight, take a look at the informational card in the seat pocket before you. Odds are it’s a comic. They work.

Medical anthropologist Dana Walrath wrote in the introduction to her graphic memoir, Aliceheimer’s that, “Around the world, comic artists, caretakers, parents, and assorted onlookers are taking up their drawing tools, pens, papers, scissors, and computers to depict illness and ways of being human that have been stigmatized. This is Graphic Medicine.” If you are interested in Graphic Medicine and the potential uses of comics in health and health policy, visit www.graphicmedicine.org. If you are in the Seattle area, consider attending some of the public events of our annual international conference this coming week which will be held at the Seattle Public Library Main Branch Thursday June 15 through through Saturday June 18th. More information is available here. Let’s get drawing, reading, and sharing more comics about the impact of health policy that aims to benefit the already advantaged and leaves the most vulnerable lacking basic care. No experience necessary.

MK Czerwiec, RN, MA is a Senior Fellow of the George Washington University Center for Health Policy and Media Engagement. She is also Artist-in-Residence at the Northwestern Feinberg Medical School. Her graphic memoir, Taking Turns: Stories from HIV/AIDS Care Unit 371 was recently published by Penn State University Press. She is also a co-author of the Graphic Medicine Manifesto and with Dr. Ian Williams co-runs GraphicMedicine.org

Story is an important part of healing.