Nursing Students as Writers

A new writing course for Hunter–Bellevue School of Nursing graduate students got off to a great start this past Thursday evening. CHMP poet-in-residence Joy Jacobson and I will teach the class for the next four and half weeks of Summer Session II. Our immediate goal is to help the students sharpen their skills in writing—scholarly writing, blogging, and narrative writing—and in on-the-job communication. But we also hope to motivate students to invest more energy in their writing by developing a daily writing practice focused on their clinical and personal experience. We’ll supplement this work by close reading of literary and scholarly texts that deal with the experiences of illness and caregiving.

The combination of reflective writing and close reading is an adaptation of the pedagogical approach used in the emerging field of narrative medicine. The mission statement of Columbia University’s Program in Narrative Medicine provides a good introduction to the aims of this discipline:

Narrative Medicine fortifies clinical practice with the narrative competence to recognize, absorb, metabolize, interpret, and be moved by the stories of illness. Through narrative training, the Program in Narrative Medicine helps doctors, nurses, social workers, and therapists to improve the effectiveness of care by developing the capacity for attention, reflection, representation, and affiliation with patients and colleagues. . . .

(I wrote a previous blog post about a presentation given by the founder of the Columbia program and one of the pioneers in this field, Rita Charon, MD, PhD. An extensive bibliography with links to several publications by Charon and others can be found here.)

We adapted our guidelines for developing a daily writing practice from Writing as a Way of Healing: How Telling Our Stories Transforms Our Lives, a fascinating book by Louise DeSalvo, professor of English at Hunter and leader of a memoir workshop in the MFA Writing Program. (She also blogs at Writingalife’s Blog.) Anyone interested in writing as a means of exploring the self will find sound advice and much food for thought in this book. DeSalvo writes

This book is an invitation to engage with your writing process over time in a way that allows you to discover strength, power, wisdom, depth, energy, creativity, soulfulness, and wholeness. . . . to use the simple act of writing as a way of reimagining who you are or remembering who you were. To use writing to discover and fulfill your deepest desire. To accept pain, fear, uncertainty, strife. But to find, too, a place of safety, security, serenity, and joyfulness. To claim your voice, to tell your story. And to share the gift of your work with others and, so, enrich and deepen our understanding of the human condition.

These are not mere self-help bromides. DeSalvo draws on a growing body of evidence from research conducted by James W. Pennebaker and others that demonstrates the beneficial psychological and physiological effects of a specific kind of writing about disturbing or powerfully emotional events. According to DeSalvo, Pennebaker discovered that “to improve health, we must write detailed accounts, linking feelings with events [the emphasis is DeSalvo’s]. The more writing succeeds as narrative—by being detailed, organized, compelling, vivid, lucid—the more health and emotional benefits are derived from writing.” (Pennebaker’s Web page at the University of Texas, Austin, has an extensive bibliography of his research, with links to free downloadable files. Click on Publications. He is also the author of Opening Up: The Healing Power of Expressing Emotions.)

DeSalvo and others, such as Sara Baker, who facilitates what she calls Woven Dialog creative writing workshops with patients at the Loran Smith Center for Cancer Support in Atlanta, Georgia, and elsewhere, also note an important caveat: this kind of writing practice, especially at the beginning of the process, can stir up strong negative feelings, particularly among those who have experienced real trauma (for example, those who have survived cancer or violent abuse). It’s important not to push oneself too far; or, as Baker writes: “We must not use our work to retraumatize ourselves or put ourselves in danger.”

Baker encourages imaginative writing—using the tools of fiction and poetry to offer what she has called “an oblique route” that may give a survivor of trauma “more freedom to connect with emotional and often buried truths” than the more direct route of memoir would provide. (Sara Baker blogs at Word Medicine.)

At the first class meeting last week, students dove right into a guided writing exercise called “My Least-Favorite Patient or Colleague.” First, each of us made up a list of nouns or adjectives beginning with the letter ‘B’ that described the person we had in mind; then another list of words beginning with the letter ‘S’ that described how that person made us feel; and a third list, of verbs or verb phrases beginning with the letter ‘T,’ that described what we would like to do to or with that person. Then, based on this material, each of us wrote a simple “list poem”—that is, a poem in which each line begins with the same word or phrase (such as “I remember…”). The last line has to have a strong twist or surprise, something like the punch line of a joke. And to cap it off, the title of the poem is written last (and is often humorous or ironic in retrospect). You can imagine how this little exercise got the juices flowing.

Stay tuned. We may be publishing some of our students’ writing on the CHMP blog in August.

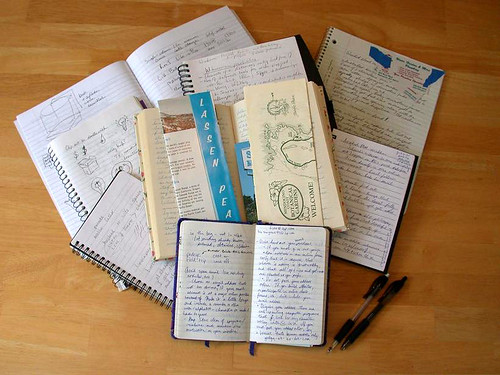

Notebook collection, a photo by Dvortygirl on