Rural Hospitals

I just wrote a blog post for JAMANews Forum on the closure of rural hospitals. It describes why they close and discusses policy responses that could ensure that these hospitals are able to promote the health of their communities in myriad ways, not just by providing acute care services.

As it was being posted, Trump released his proposed budget. If passed, it will accelerate the loss of hospitals in rural communities. When hospitals close, it severely impacts the economic survival of rural communities. The proposed cuts will not “make America great again.”

According to USAToday:

White House Budget Director Mick Mulvaney said it is a taxpayer-focused budget that seeks to help those who really need government assistance while nudging others who need to “get off of those programs” and “get back in charge of their own lives again.” The budget would also make room for tax cuts estimated to cost $6.2 trillion over 10 years, with more than three-quarters going to the top 20% of taxpayers.

But various sources are weighing in to counter the rhetoric that the budget cuts are in the interests of taxpayers in rural America.The proposed budget will damage the health of rural communities in a number of ways. Here are three:

- It will slash Medicaid funding beyond the cuts already proposed in the House-passed American Health Care Act. Some rural areas will be the hardest hit. Rural areas have lower household income levels and higher rates of poverty than urban areas. The expansion of Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare) helped poor men gain health care coverage for which they had previously been ineligible.

- It will eliminate telehealth funding. Telehealth is crucial to linking rural communities to specialty services. In my JAMA blog, I noted that the survival of rural hospitals in dependent, in part, on being part of a larger health system that has the specialty services, as well as intensive care. Telehealth enables rural hospitals to remotely access specialty services, including consultations on emergency care. Nurse Kristi Henderson, DNP, RN, FAAN, recognized this years ago when she built TelEmergency, an emergency telehealth service through the University of Mississippi to the remote and underserved rural communities of the state.

- It would reduce or eliminate other federal grant programs that help rural hospitals to survive. Rural hospitals have a very thin operating margin, so even small reductions in funding can cripple them and lead to closure. In addition, the budget would slash funding for the state offices of rural health, undercutting communities’ efforts to monitor and address the impact of cuts on health.

Lots of political commentators are pointing out that Trump’s budget would hurt most those who voted for him, including people in rural America. It’s up to Congress to pass a budget. What they pass will determine whether these communities will die or thrive in Trump’s America.

I just wrote a blog post for

Nurses and Patients and Plagiarism, Part 2

In the six years or so that I’ve blogged at HealthCetera, I’ve written about the use of reflective writing in clinical practice and education, and I’ve examined poems that elucidate aspects of health and health policy. And in that time the post of mine that has been viewed most often—by far—is one I wrote three years ago, “Nurses and Patients and Plagiarism: The Consequences Aren’t Merely Academic.”

Why is there such an enduring interest in plagiarism? My post looked at a couple of literature reviews that suggest academic dishonesty among nursing students may have implications for ethical nursing practice. A new search shows the problem is far from resolved.

Last November, for example, the UK weekly journal Nursing Standard reported the results of its investigation that found thousands of UK nursing students had committed academic fraud, 79% of the cases involving plagiarism (the article is free but requires a login).

And in March Australian researchers Lynch and colleagues published an integrative review on plagiarism in nursing education (login required) in Journal of Clinical Nursing. The study illuminates several fascinating aspects of the plagiarism problem in nursing:

- Students’ cultural or language background does not affect their likelihood of plagiarizing.

- Many nursing students simply do not understand the basics of referencing and paraphrasing.

- Inadvertent or accidental plagiarism is common.

- Students are more likely to plagiarize if they are at risk of failing a course.

- As unethical behavior in academia becomes “neutralized” and then “normalized” to nursing students, they are more likely to continue to engage in unethical behavior, with serious implications for clinical practice.

- Some faculty find it an “enormous burden” to deal with academic dishonesty.

- The threat of punishment has not reduced plagiarism in nursing education.

That last point seems important to emphasize. Just today a writer in Inside Higher Ed, Jennifer A. Mott-Smith, suggests that unless a student submits a paper she paid someone to write or copied and pasted it entirely, academic plagiarism should not be punished—that it instead should be seen as a teaching opportunity to help students “continue to practice the difficult skill of using sources.”

That has been my approach as a writing instructor with nursing students. But this can’t mean pretending it’s not happening. Rather, it requires something extra from nursing faculty and institutions—namely, real time spent on teaching writing as a process in which the student learns to think. Otherwise, the copying culture will not abate.

I’d like to hear from others, both nursing students and faculty. Is plagiarism an issue for you? How have you handled it?

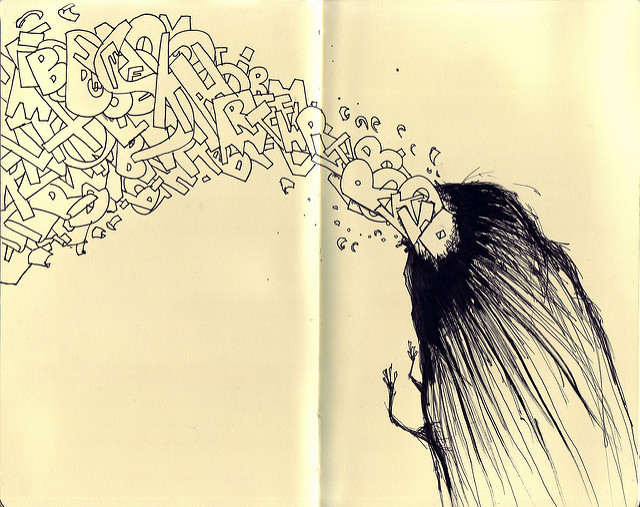

Image source: Matt Saunders, flickr

In the six years or so that

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

- 40

- 41

- 42

- 43

- 44

- 45

- 46

- 47

- 48

- 49

- 50

- 51

- 52

- 53

- 54

- 55

- 56

- 57

- 58

- 59

- 60

- 61

- 62

- 63

- 64

- 65

- 66

- 67

- 68

- 69

- 70

- 71

- 72

- 73

- 74

- 75

- 76

- 77

- 78

- 79

- 80

- 81

- 82

- 83

- 84

- 85

- 86

- 87

- 88

- 89

- 90

- 91

- 92

- 93

- 94

- 95

- 96

- 97

- 98

- 99

- 100

- 101

- 102

- 103

- 104

- 105

- 106

- 107

- 108

- 109

- 110

- 111

- 112

- 113

- 114

- 115

- 116

- 117

- 118

- 119

- 120

- 121

- 122

- 123

- 124

- 125

- 126

- 127

- 128

- 129

- 130

- 131

- 132

- 133

- 134

- 135

- 136

- 137

- 138

- 139

- 140

- 141

- 142

- 143

- 144

- 145

- 146

- 147

- 148

- 149

- 150

- 151

- 152

- 153

- 154

- 155

- 156

- 157

- 158

- 159

- 160

- 161

- 162

- 163

- 164

- 165

- 166

- 167

- 168

- 169

- 170

- 171

- 172

- 173

- 174

- 175

- 176

- 177

- 178

- 179

- 180

- 181

- 182

- 183

- 184

- 185

- 186

- 187

- 188

- 189

- 190

- 191

- 192

- 193

- 194

- 195

- 196

- 197

- 198

- 199

- 200

- 201

- 202

- 203

- 204

- 205

- 206

- 207

- 208

- 209

- 210

- 211

- 212

- 213

- 214

- 215

- 216

- 217

- 218

- 219

- 220

- 221

- 222

- 223

- 224

- 225

- 226

- 227

- 228

- 229

- 230

- 231

- 232

- 233

- 234

- 235

- 236

- 237

- 238

- 239

- 240

- 241

- 242

- 243

- 244

- 245

- 246

- 247

- 248

- 249

- 250

- 251

- 252

- 253

- 254

- 255

- 256

- 257

- 258

- 259

- 260

- 261

- 262

- 263

- 264

- 265

- 266

- 267

- 268

- 269

- 270

- 271

- 272

- 273

- 274

- 275

- 276

- 277

- 278

- 279

- 280

- 281

- 282

- 283

- 284

- 285

- 286

- 287

- 288

- 289

- 290

- 291

- 292

- 293

- 294

- 295

- 296

- 297

- 298

- 299

- 300

- 301

- 302

- 303

- 304

- 305

- 306

- 307

- 308

- 309

- 310

- 311

- 312

- 313

- 314

- 315

- 316

- 317

- 318

- 319

- 320

- 321

- 322

- 323

- 324

- 325

- 326

- 327

- 328

- 329

- 330

- 331

- 332

- 333

- 334

- 335

- 336

- 337

- 338

- 339

- 340

- 341

- 342

- 343

- 344

- 345

- 346

- 347

- 348

- 349

- 350

- 351

- 352

- 353

- 354

- 355

- 356

- 357

- 358

- 359

- 360

- 361

- 362

- 363

- 364

- 365

- 366

- 367

- 368

- 369

- 370